From Conquest to Care: Rethinking the Cabinet of Curiosities

- Cayman Islands National Museum

- Sep 30, 2025

- 3 min read

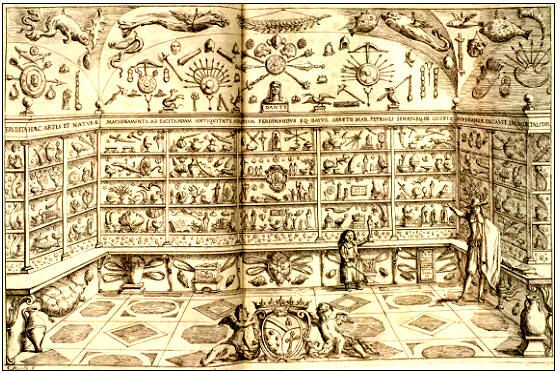

The Cabinet of Curiosities, also known as the Wunderkammer, first emerged in 16th- and 17th-century Europe. Wealthy collectors filled cabinets and entire rooms with ‘exotic’ objects, including natural history specimens, artworks, and cultural treasures from foreign lands brought back from overseas voyages. To its audiences, which were limited at that time, these collections were windows into unusual and fascinating worlds, but this sense of wonder concealed a complex power-play.

The rise of the Cabinet of Curiosities was closely tied to colonial expansion. As European empires spread globally, objects were extracted, often by force or outright theft, from the lands they conquered and transported back to Europe. Their context and meaning were reshaped to suit collectors’ desires. By deciding how the world should be ordered and displayed, European elites reinforced their own power. Knowledge, in this sense, became a tool of empire.

Closer to home, one example of this kind of collecting was practised by Sir Hans Sloane. Sloane travelled to Jamaica in 1687 to serve as physician to the colony’s new governor, the Duke of Albemarle. During this time Sir Hans Sloane amassed more than 800 plant specimens, as well as animal specimens, and other ‘curiosities’, with the help of enslaved Africans and other English planters. On his return, he married into the Jamaican plantocracy, gaining further wealth from the labour of enslaved people. This allowed him to expand his already vast holdings by purchasing artefacts from other collectors. Following his death in 1753, Sloane’s collection was bequeathed to King George II, on the condition that a new and publicly accessible institution would be created to display it. Thus, Sir Hans’s collection became one of the foundational collections of the British Museum.

But the story of the Cabinet doesn’t end there. Beyond the elites who popularised the Wunderkammer, other individuals (at the time, and later) gave collecting a new meaning. In the Cayman Islands, for example, collecting became less about conquest and power over other cultures, and more about preservation, memory, and identity. Private collectors such as Ira Thompson, who began collecting ‘odds and ends’ in the 1930s, dedicated themselves to documenting Caymanian life in its entirety, from the extraordinary and unusual to the simple and mundane.

Thompson’s intentions were vastly different from those of European elites. Rather than extracting objects to assert dominance over other cultures, he worked to build a lasting image of the Cayman Islands through its material culture. His “Kiemanos Museum” on Crewe Road was an open-air collection where everyday items sat alongside rare finds, each one helping to tell the story of how Caymanians lived, worked, and celebrated. His collecting also had a strong nationalist dimension: Thompson, a hobbyist, birdwatcher, and taxi driver, was passionate about preserving Caymanian heritage to connect past, present, and future Caymanian and international generations. His work as a taxi driver, at a time when tourism and globalization were transforming the Cayman Islands, likely provided him with a unique role as a bridge between local traditions and international audiences. His Kiemanos Museum became a frequented attraction for both Caymanians and visitors could explore the islands’ history and culture.

The legacy of that work lived on, later helping to shape the Cayman Islands National Museum, which continues to serve as a hub for celebrating and protecting Caymanian heritage. In 1979, the Cayman Islands government purchased his collection, which became the nucleus of the Cayman Islands National Museum. What began as one man’s personal effort has since become a national resource, anchoring the museum’s mission to preserve and interpret Caymanian heritage.

This contrast shows how powerful context can be. In Europe, cabinets of curiosity were about control and spectacle. In Cayman, Thompson’s cabinet was about memory and identity. One silenced cultures; the other gave them voice. Today, as museums wrestle with questions of ownership and representation, Thompson’s example feels especially relevant. Collecting can be an act of care, honouring histories, preserving stories, and keeping community memory alive.

The Museum is planning an exhibition on the Ira Thompson Collection for 2026.

References:

British Museum (n.d.) Sir Hans Sloane. Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/sir-hans-sloane (Accessed: 25 September 2025).

Cayman Islands National Museum (2025) The Ira Thompson Collection. Available at: https://www.museum.ky/post/the-ira-thompson-collection (Accessed: 25 September 2025).

Royal Collection Trust (n.d.) Wunderkammer: Cabinet of Curiosities. Available at:https://www.rct.uk/collection/themes/trails/wunderkammer-cabinet-of-curiosities (Accessed: 25 September 2025).

Comments